Every watch has the same purpose: you look at the thing and it tells you the time. That’s the baseline.

But within the world of mechanical watches, there are genus, species, and families of watches loosely related to who, or what, they are made for, and the design features that go along with that.

We’ve talked about space watches and what they can do.

And when most people think about a “nice watch” they tend to think of a classic diver, like a Submariner or a Seamaster, which is good to go a couple hundred meters down, and usually has a basic timing bezel.

There are racing watches, with a chronometer stopwatch as an added complication, and engineer’s watches, which put a big premium on resisting electromagnetic fields that are murder on all those tiny springs and coils.

But what makes a pilot watch? It’s mostly a question of design aesthetics, rather than some technical capability. I mean, unless you really suck at flying, water resistance is not exactly a must.

And I love them. They are my sweetspot, my high school crush, the thing I default to.

Maybe they aren’t what you’d call pretty. But you’d be wrong, because beyond the baseline reliability of the movement inside any watch, pilot watches are all about form as function: perfect, unapologetic, simplicity.

There’s an argument that they are the purest kind of watch design there is. Let me explain.

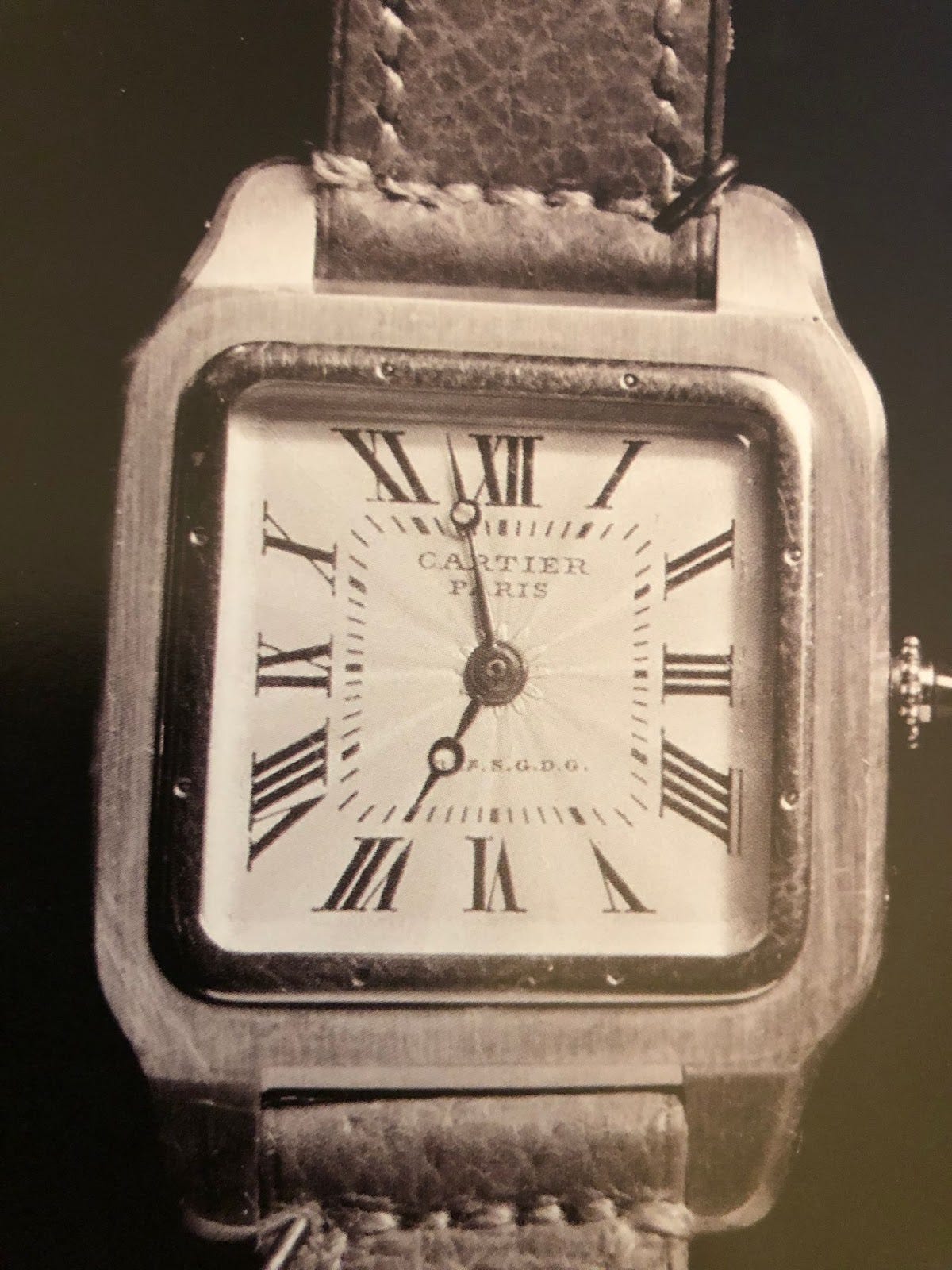

Okay, basic principles. A pilot watch is exactly that—designed specifically for someone flying a plane—and it goes back to the very beginning of aviation. The idea of a “wristwatch” was, in the 19th century, basically for the ladies, and toffee-nosed Eurotrash at that.

Men had pocket watches. They were functional, they could tell the time, and were a romantic place to keep that lock of hair from the girl you were stalking. Bonus: They came on a chain you could use to dangle all your Freemasonic tchotchkes to let everyone know you liked to wear an apron and get spanked after the bank closed. It was a weird time.

But you can’t check a pocket watch while you’re wrestling with the stick of a prototype biplane, so early pilots literally strapped their full sized pocket watches onto their wrists—over their jackets.

It worked surprisingly well and most of the defining characteristics of a “pilot watch” were set this way.

Ironically, the first actual purpose-made pilot’s watch, the Cartier Santos-Dumont (named after the Brazilian pilot it was made for) has almost none of these, and while it’s still a classic design, it’s really more of a dress watch.

So what makes a pilot watch? In a word: legibility.

The first military pilots navigated using a compass and a watch and it needed to be VISIBLE, all caps, above everything else. We are talking a seriously oversized case, high contrast dials and big, bold, Arabic numerals. While luminescence came in eventually, it wasn’t a big deal to begin with because if the weather was nasty or it was dark, you were probably grounded.

A pilot watch tells you the time, and it doesn’t wait for you to ask. Done well, when you wear one in normal life it’s so readable in your peripheral vision that you rarely check it—you just know the time without having to look.

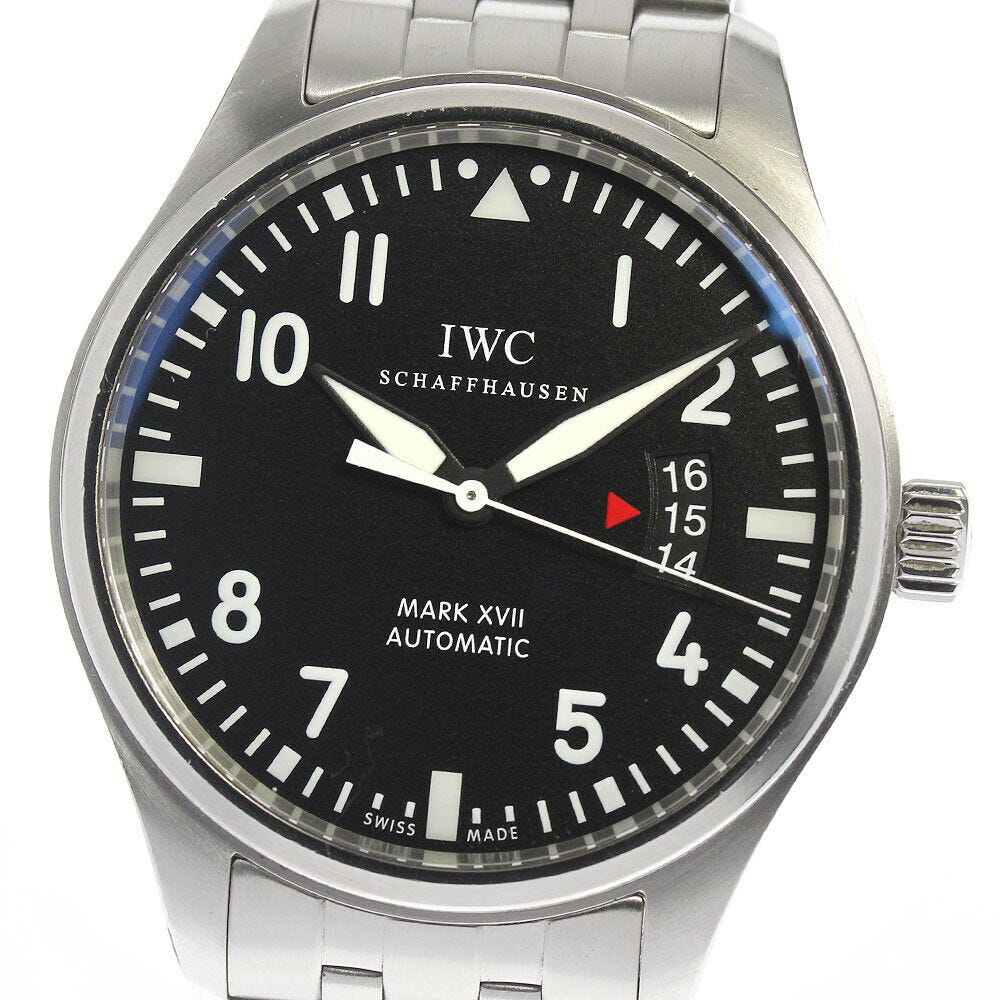

The design heyday of pilot watches was the two world wars and the inter-war years, with the Germans leaving as big a mark on the style as they did on East London. The B-Uhr design is probably to pilot watches what the Submariner is to dive watches: It’s the one everyone recognizes:

Black dial, white numbers, big font, nothing to distract you. A giant crown so you could wind and set the thing with gloves on.

And see that triangle at 12 o’clock? Absolute design hallmark.

It serves two functions: when you’re in crappy lighting and wrestling with the controls, you can tell at a glance which way is 12 — and as lume came in this would often be the only glow in the dark part of the dial, along with the hands.

The secondary function was it aided visibility in tracking the second hand hitting the top of the hour, which was a help for synchronization by radio for formations literally on the fly.

IWC - The OG

A lot of companies in Germany and Switzerland turned out variations of this design throughout the war for use by those playful carpet bombers of the Luftwaffe. After the war, there was less call for them and German chic was not exactly en vogue. But if the design has endured to outlive those associations, it is mostly down to my favorite watch company, IWC, and their Big Pilot, which they first made in 1940 but brought back as their centerpiece about 30 years ago.

When I was a kid in my first big-boy job, I was working for a political party and, being the low man on the totem pole, my desk was used as a dumping ground for auction prizes for the big annual gala. For a month, I had a Big Pilot in a display case on my desk and I absolutely fell in love with it. It was how I got into real watches.

These are, I would argue, pound for pound, the purest kind of wrist watch you can get. Totally readable, absolutely uncomplicated, function as art. Sometimes you’ll get a small seconds sub dial instead of a third hand, sometimes a seven-day indicator. But at its core this is a big, clean, watch: uncompromising, unimprovable.

Looking at this thing is a moment of zen and it’s probably the watch that has kept IWC in business. I love it, even if I can’t come close to affording one.

IWC, along with a bunch of other Swiss companies, sold to both sides of the war—it’s Switzerland after all. The other mainstay of their pilot’s range is the Mark series, all riffs on the Mark XI, which became standard UK military issue in 1948.

The proportions of the watch are still there, as is the basic design language, but the whole package is a bit less oversized than the German flavor.

We’ve had five other iterations of the Mark series since the original, and while they are all fine, I could write an entire post on how each one has something wrong with it—a badly-done date window (which you don’t even need on a pilot watch), poorly placed markers, always something.

I used to think IWC was doing this on purpose. That they were deliberately screwing up something, always something different, on the Marks—just to push people toward the more expensive Big Pilot. But I really can’t complain about much with the most recent Mark XVIII, which is still $4,500.

That said, for a few hundred bucks more you can get what I think is maybe the best value watch they do: the Spitfire. I love this watch. Everything good about the Marks, but done better. And a fully in-house movement. It’s just a better class of watch for marginally more money.

But don’t let my IWC obsession put you off.

Pilot watches are tool watches, and frankly, while IWC does a great job, even their best movements aren’t batting in the same league as the best of Omega or Rolex, and certainly not Grand Seiko. If your kink is shaving that extra +/-2 seconds of accuracy a day, pilot watches aren’t going to be your thing. The biggest part of the tool is the dial design, and IWC didn’t invent that and doesn’t have a monopoly on it, either.

Plenty of German brands, like Laco or Stowa, have the same historical track record as IWC (not that that’s a lot to be proud of when we’re talking about the airborne bad guys of history) and are making classic B-Uhr designs for half the price. And, frankly, while there is a difference in quality, a lot of the price gap is down to marketing.

And don’t sleep on other brands either.1

Hamilton was a heritage American brand out of Lancaster Pennsylvania, until they were bought by the Swiss in 1969 and ended up as a tentacle on the Swatch Group octopus. At different points, they were official suppliers to the USAF and the RAF, and, while some of their stuff is way too wacky for me, they are as legit as anyone when it comes to their old-school military field and pilot watches.

My wife gave me a Spitfire chronograph as an engagement present, and (very shortly) after the baby it’s the one thing I’d rescue if the house was on fire. But for day to day wear? I’ve got a big ass Hamilton khaki pilot in one of my favorite variations: the inverted minute/hour display.

Why do this? Well, if you are using the watch to plot your speed/time/direction of travel, you actually care a lot more about the minutes than the hour, so the minute markers get the big, bold treatment and the hours are shrunk down to a sub-dial display. It hits the absolute core of the pilot watch design concept—at a glance functional time reading.

This variation has been around for almost as long as purpose-designed pilot watches have existed; pretty much all the big brands who do pilot watches have one. It’s the purist’s choice. I’m a big fan.

But to prove my point about the quality of a pilot’s watch being about good design, not just a big price tag, consider these versions from IWC and Rolex. Notice anything about the numbers?

Check out one o’clock/five minute mark. Both the Rolex Air-King and IWC have a “5”, the only single digit on the dial. It looks unbalanced, right? Once you see it, it kind of pisses you off.

This year at the Watches and Wonders expo, Rolex released a new Air-King with “05” on the dial and everyone was oh so impressed—inspired they said, totally changes the watch face, what attention to detail, what a value for symmetry!

Now look back above. Hamilton was doing this years ago. Sure, Rolex waterproofed the crap out of theirs, and it is a good 3 or 4 seconds more accurate. But they didn’t get the basics of the dial right.

So I have to concede that everything above is what I consider a pure pilot watch. But there are a lot of pilot watches out there, in the sense that they are made for people who fly planes, with a totally different design language and functionality.

The advent of jets, super sonic flying, and a bunch of other stuff brought in a ton of watches for pilots that were as tech'd out as their new planes. Some of them I like—like IWC’s Top Gun line.

Others I hate.

And I mean Breitling. I hate Breitling. And I hate the Navitimer.

Brought into production in the ‘50s, this was their follow-up to their famous Chronomat and it became their signature pilot watch, fully endorsed by the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association. It was launched boasting, compared to the Chronomat, “an even more complex bezel with logarithmic, double rotating slide rule scale, with which fuel consumption, rate of climbing or sinking and average speeds can be calculated quickly.”

Quickly? Are you forking kidding me? You need to take AP calculus just to understand what the hell this thing does and a magnifying glass if you actually want to do it.

Now maybe I’m just bad at math and this is all basic stuff to everyone else. If so, good for you all but I never made it past Algebra II and this does not strike me as something anyone is using in a hurry.

But more to the point: It’s a hot mess to look at.

The zen of a pilot’s watch is calm, uncluttered, clarity of vision. It’s like ikebana, the Japanese art of flower arrangement; at its most basic level it involves the triangular composition of three main elements which bring balance and harmony and focus—never distraction.

The Navimeter’s dial is all over the place, it’s crazy, it’s incoherent, it’s aggressive, it’s unsettling. I cannot understand why people go for it. It’s the Amber Heard of watches.

More to the point, I don’t know where to look. It makes me twitch. I’d crash the plane trying to figure out what time it was. No thanks.

Just to round off, I want to say something nice about Rolex.

Sure, they bit down hard on the Air-King as I said above. But, actually, even when they corrected the 05 this year, they screwed something else up by adding crown guards—which is a no-no for pilot watches because you’re supposed to have a freestanding, oversized crown you can easily work with gloves on.

But they did give the world the most iconic GMT ever, which, despite being universally referred to as the Pepsi design, because of the red/blue day/night 24 hour bezel, was made for PanAm pilots, hence the colors.

The GMT Master was a badass watch, no complaints from me. And the current GMT Master II is pretty iconic, that stupid Mercedes hour hand notwithstanding.

But no watch better captures what’s happened to Rolex in the last few decades—going from standard-issue for commercial pilots to more than $10k at retail (close to triple that second hand, thanks to their larcenous authorized dealer set-up) and with . . . let’s call it very marginal improvements in relative quality.

Such a shame.

I haven’t talked about Bremont. I have a lot of thoughts on them, and they are… mixed. There just isn’t the space here.

Boy, I'm with you on Breitling. Their watches are, well, there's a Yiddish word for it: Ungapatchka. To me that describes most of their watches. For those non-speakers of Yiddish, the word is " an adjective that describes something which is overly ornate, busy, ridiculously over-decorated, kitch, and garnished to the point of distaste. Doing senseless things.

I appreciate the reply in the previous article’s comment and the more thought out essay on the subject matter. Exactly what I subscribed for. Thank you, sir.